Return to Syracuse

Our dual political nature can be exploited to create an effective Utopia based on AI-enhanced scientific realism.

1. Introduction

Modern humans living in centralized polities with regulated market economies are, on average, experiencing longer, healthier, and more secure lives than our recent ancestors. Infant mortality has dramatically declined, and global poverty, along with violent deaths, is being reduced. Although out of Eden, material efflorescence and increased human cooperation have led to the creation of welfare states, more inclusive societies, and pacified international relations (Pinker, 2017).

But progress inevitably comes with a price.

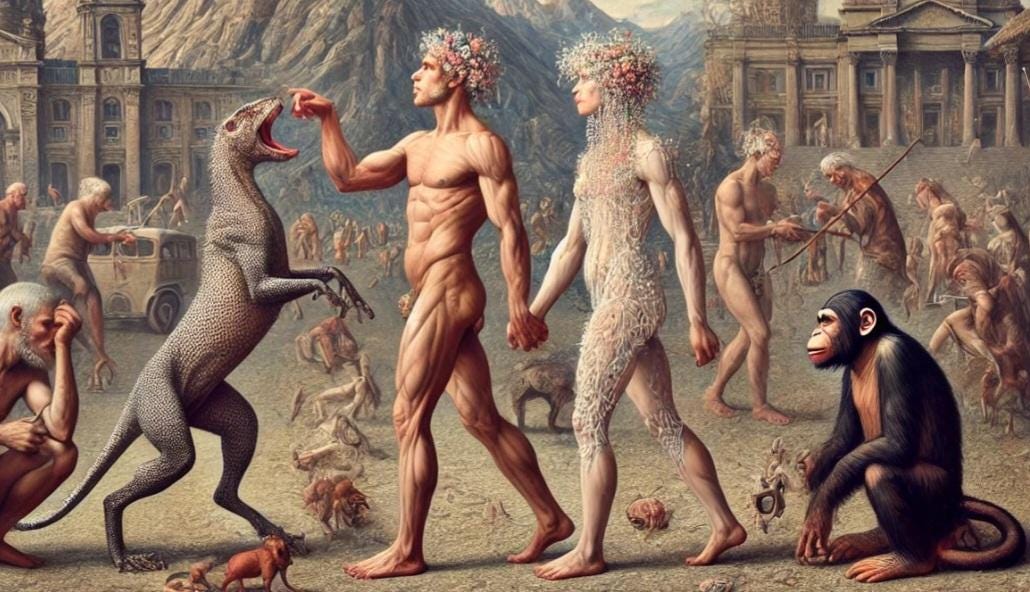

Due to the differing pace of cultural and biological evolution in behaviorally modern humans, particularly during the last age of scientific, technological, and social revolutions, we now find ourselves simultaneously 1) unadapted to highly artificial and evolutionarily novel environments and 2) overexposed to fabricated superstimuli designed to exploit deeply ingrained psychological adaptations, ranging from sugar and pornography to synthetic drugs and pop music. Contemporary humans, apparently not so “solitary, poor, nasty and brutish” after “the great divergence”, are “mismatched” (Li et al., 2017). Paraphrasing John Carter: “If you’re anything like us, the world we live in feels increasingly alien every day.”

Box 1. A term coined by ethologist Niko Tinbergen and developed by Konrad Lorenz, supernormal sign stimuli are classically defined as “exaggerated/heightened imitations of naturally evolved phenomena/objects that exert a stronger attraction/desire on their target audience than the natural phenomena/objects themselves” (Barrett, 2010). A cuckoo egg, similar in appearance but larger and brighter, is a well-known example.

2. Born ultra-socials

Animal societies represent a unique evolutionary phenomenon, a 'great transition' (Wilson, 2009) and perhaps a cosmic singularity in the level of biological organization, paralleled only by the emergence of conscience. This decisive shift has its origins approximately 200 million years ago, back in the early Cretaceous period when the first known species of eusocial termites arose. The ultra-sociality of modern humans (Tommasello, 2014), which co-evolved with the origins of language -another of Wilson’s ‘great transition’- and was likely initiated in its rudimentary stage by Homo habilis around two million years ago, is built upon this deep Darwinian history predating the establishment of political communities.

Assuming that modern humans are political and self-domesticated (Bednarik, 2020, Wrangham, 2019), ultra-social animals —'more of a political animal than bees or any other gregarious animals,' according to Aristotle—there is no reason to believe that socio political traits are immune to the double condition of unadaptation and superstimuli overexposure. Therefore, at least part of the history of political ideas, ancient and modern, should be explained by the interplay between evolved human traits and potential exploiters. As noted above, this process has a deep pre-history that predates contemporary political schemes but has accelerated since the invention of the press and especially since the diffusion of post-literary informational techniques in the 21st century. For example, the latter phenomenon labeled as political polarization -meaning a growing ideological gap between liberals and conservatives- and the surge of political extremes can be studied, in part, as manifestations of exploitative memes (King, 2020) through the deliberate use of communication mechanisms like selective bias, filter bubbles and echo chambers (Otieno, 2024). The influence of supernormal political stimuli should accordingly be studied to explain shifts in the political cycle, along with usual causal suspects like war, famines, subversion, impoverished classes, or overproduction of elites.

“A very smooth talker, very convincing.”

It’s no secret that modern humans are impressionable animals, routinely exposed to Machiavellians and conmen from all parties since time immemorial. However, today’s proliferation of communication technologies, global media, and popular AI likely exacerbates unwelcome tendencies.

Freed from the moral and literary national canon characteristic of humanist societies based on 'books and letters', post-literary artificial superstimuli are produced and dispatched almost unrestrainedly now to targeted audiences in post-canonical, globally ultra-connected, and locally fragmented communities where not even the surviving goalkeepers of traditions can break the modernity spell.

3. An hypothetical case study: Supernormal conservatism

Samuel Huntington (1957) famously proposed a tripartite division of conservatism as an ideology, beginning with 1) an aristocratic theory indissolubly associated with the ancien régime, characterized by “landed interests, medievalism, and nobility”; 2) an autonomous conservatism, defined “in terms of universal values such as justice, order, balance, and moderation” and 3) a situational conservatism as a “system of ideas employed to justify any established social order.” Huntington also made a sharp distinction between the conservative and the unsuccessful conservative, i.e., the reactionary. The former, while apparently remaining attached to the ideals of an old and venerable traditional philosophy, ends up romanticizing a past—a “golden age which never in fact existed”—thus becoming a de facto radical.

“Dichosa edad y siglos dichosos aquellos a quien los antiguos pusieron nombre de dorados…”

This “golden-age” neo-reactionary may be redefined as an instance of the political supernormal, an exaggerated imitation of “normal” Burkean ideas surrounding religiousness, community, and hierarchy. At that point, the evolved conservative becomes a mismatched Huntingtonian, a “radical” sharing many features with the political fringes and ironically being more akin to Utopian and revolutionary thinking than to “normal” conservatism. Rather than a genuinely “redpilled” revolt against the modern world, neo-traditionalist and neo-populist branches of supernormal conservatism constitute, in this respect, a distinctively postmodern phenomenon founded on the systemic exploitation of the “conservative syndrome” (Stankov, 2017) -which is likely contributing to perpetuate “the right’s stupidity problem”- and too often an “aesthetic movement that aims to attract youth through edgy transgression rather than a serious pursuit of political change.”

4. The rise of effective Utopians

Box 2. The Philosopher King presented himself in the πιστολὴ Ζ as an aspiring civic bodhisattva, someone who has attained individual enlightenment but choose to liberate the community from the perpetual cycle of regime-change in misgoverned cities, whose constitutions “must be constantly changing, tyrannies, oligarchies and democracies succeeding one another”.

While the term "Utopia" did not appear until Thomas More's essay in 1516, the concept has been widely used since then in political philosophy to describe the proposition of an ideal society. A political Utopia can be defined as a designed social order based on discernible principles, whether rational or supra-rational, guided by perfect rule; in other words, a system of social organization such that humans are liberated from the political cycle of decaying regime-change. In the Western tradition, this traces back to Plato's pioneering writings (in particular, The Republic, 380 BCE), a stance balanced by Aristotelians, who emphasize the idea of an organic political order based on human nature and mixed government. This is, of course, an oversimplification, or to be more precise, a description of basic political philosophy as it was understood by the main adherents of the great political philosophers, which is not necessarily the way it was understood by the originators themselves (*).

We are nevertheless entering an era where big data, AI systems, and the ancestral human libido dominandi can coalesce to optimize the Platonic-inspired anthropotechniques (Peter Sloterdijk’s seemingly dangerous idea) required to make a stable Utopia. This poses a potential existential threat, risking not just the American liberal order or “the bedrock values of Europe”, but perhaps all existing variations of human polity, even though it remains to be seen how this contemporary ‘arm race’ between global but multipolar actors over IA-Systems would affect the balance of world power.

What is certain is that the emergence of the techno-scientific paradigm will have a deep and unseen impact. Approaches grounded in evidence-based, well-replicated research areas such as evolutionary psychology, behavioral science, psychometrics, neuroscience, and genetics now constitute a potentially effective toolkit for renewing ideological frameworks. Predictably, the result will surpass previous anthropotechniques, in particular the radical environmentalist and blank-slatist approaches typically associated with failed Utopias of the past. In spite of repeated efforts, enormous human endeavors, and devoted fanaticism throughout the centuries, ineffective Utopians—from early 'philosopher kings' to 'scientific socialists'—failed because they did not rely on a sound theory of human political nature. For that matter, it's no coincidence that some of the areas most affected by the recent scientific replication crisis are precisely those most favored and cultivated by traditionally ineffective Utopians, such as social psychology.

But this can change. A rediscovery of human nature based on AI-enhanced scientific realism (AESR) (**), combined with sufficient power and governance centralization, and optimized anthropotechniques, makes an effective Utopia oriented toward 'Ευταξία' (‘good order’) feasible. Some preliminary evidence and real-world examples of AI applications in socio-political contexts are already known: use of chat-bots, micro-targeting and predictive analytics in political campaigns, pieces of legislation drafted by AI, AI-generated political messaging, etc, but the comprehensive impact of AI-Systems in social and political science is yet to come.

Despite the unsurprising ‘situational conservatism’ and the ideological “strength of the orthodoxy” (Warne, 2020) resisting the paradigm shift, a ‘scientific revolution’ is at the gates of the social sciences. Refined statistical and computational methods, the handling of large-scale data, the increased availability of “open science” to independent researchers, and key and specific advances in genomics (such as the discovery of ancient human genomes and the development of GWAS studies and polygenic scores to predict complex traits) consolidate the idea that humans possess an Aristotelian 'political nature' (Tuschman, 2013), although it is variable and subject to cultural and biomedical engineering.

This evolved (and evolving) nature consists mainly of: 1) a set of major selected adaptations and systemic psychological biases (fear of predators, social bonding, mate selection preferences, kin recognition, language acquisition…) that evolved primarily in what the Santa Barbara school of Evolutionary Psychology (Cosmides & Tooby, 1997) calls the evolutionary ancestral environment of modern humans; and 2) a subset of relatively minor but recent adaptations and by-products (Hawks et al., 2007, Cochran & Harpending, 2009), including lactose tolerance, skeletal and dental changes in response to new diet, variations in eye and hair color, population oscillations and secular decline in IQ (Dutton & Woodley, 2021), personality traits, genetic pacification or brain size (Frost, 2018, 2024, 2022). These novel adaptations are not necessarily species-typical, arising from distinct causes, particularly sexual selection, self-domestication and gene-culture coevolution (in terms of Cochran: “Every society selects for something”), and are in fact compatible with relaxed darwinian natural selection and mutational accumulation in the industrialized world (Woodley, 2015) -though this suggestion has been contested (Arslan et al., 2018). While this subset of human biological diversity is considered to be minor or even negligible compared to ancestral adaptations, it has significant consequences for cultural, societal, and political outcomes worldwide. This dual source of human nature—Human Nature 1; universal, ancestral, enduring and instinctual, consistent with the “Out of Africa” model, and molded by natural selection; and Human Nature 2; local, recent, plastic and de-instictualized, inconsistent with “Out of Africa”, and conditioned by gene-culture interactions—explain much about the current controversies surrounding the origins of human variation (Murray, 2020; Wade, 2014).

Box 3. The domestication of humans is an evolutionary phenomenon similar to the ‘self-domestication syndrome’ found in various species. It implies a variety of modified behavioral and physiological traits over the last few thousand years, including anatomical gracilization, feminization of the brain, extended neoteny, reduction of reactive violence, and ultra-sociality. This natural process is the true preamble to the formation of centralized/literary societies and the modern taming of humans, reflected in Sloterdijk’s concept of ‘anthropotechniques’: the art of human breeding where 'man has become the higher power for man.'

In this regard, it is now increasingly well established that variation in political ideology is heritable (Hatemi et al., 2014), correlated with physiological and cognitive individual differences, such as IQ (Edwards et al., 2024), orderly personality and disgust sensitivity (Xu et al., 2019), and even with ecological determinants like parasite stress and pathogen avoidance (Tybur et al., 2016). Taken together, all this body of evidence points to a complex but comprehensible bio-cultural anthropological model, whose predictable vulnerabilities are more exposed than ever to effective exploiters of the 'Menschenpark’.

It’s also plausible that human groups vary in terms of their relative psychological vulnerability to cultural control, with more WEIRDs (Henrich, 2020) and East asians, ultra-plastic and de-instinctualized populations (for an overview of the ‘evolution towards the blank slate’ see Macias, 2024) occupying the end of the memetic spectrum. As a result, an effective Utopia might be harder to establish outside the ecological and political domains of Western Europe, neo-Europes, and the Asian ‘Confucian’ area of influence, where human populations experienced reduced evolutionary pressures towards self-domestication and extreme cultural norm-following, which are subcomponents of Human Nature 2. This framework, in my view, offers the most likely and underestimated explanation of why all forms of Utopian political universalism have hardly fulfilled their promises, including recent and failed attempts by modern ‘state-builders’ (Fukuyama, 2004) combining ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ power to expand European republicanism in unreceptive human populations from distant and diverse ecologies.

5. Modern taming of humans

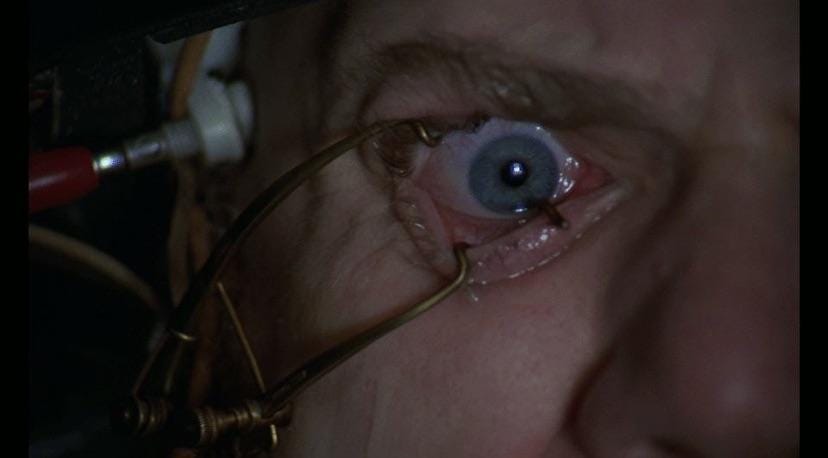

Box 4. A prototype of a Skinnerian fictional ‘Dystopia’, i.e., an ineffective Utopia. In Kubrick’s film, based on Anthony Burgess's novel, the Skinnerian behavioral treatment, so-called Ludovico Technique, ultimately fails because it doesn't address the underlying causes of criminal behavior or consider the complexities of human nature, most notably the alleged capacity for free will.

The full impact of AI systems in the modern taming of humans cannot be known in advance, but some exploratory insights can serve to orient the discussion. Detailed strategies for practical implementation, concrete steps, or pilot projects for more actionable AESR-based anthropotechniques are beyond the scope of this essay. I suggest, nevertheless, that an efficient development should comprise at least three components: 1) the recognition of a moderate hereditarian and dual theory of human political nature; 2) ‘soft’ socio-political engineering based on the smart exploitation of prosocial instincts; and 3) Science-based self-domestication of present humans.

On the first point, it should be admitted that ineffective utopians caused immense but limited trouble because, at the end of the day, they were wrong, and consequently were unable to escape from the classical political cycle and political decay (for an updated theory see Huntington, 1965; Fukuyama, 2014).

While the most cited reference of the political misuse of science is the eugenics movement in the 20th century, due to its highlighted association with Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, there are other examples with varying ideological justifications. The criminal record of ineffective Stalinists, for instance, is extensively documented and turns out to be inseparable from the theoretical shortcomings of Marxist theories, radical environmentalism and explicit pseudoscientific stances like Lysenkoism. More recently, ecologist Utopians in search of a ‘toxic-free’ society persuaded Sri Lanka’s president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, to ban the importation and use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides in 2021. The move was part of an effort to transition the country to 100% ‘organic agriculture,’ based on unverified claims about the benefits of organic farming for health and the environment, and resulted in a major economic, agricultural, and social crisis, reversed only after months of protests and political instability.

Secondly, AESR-based anthropotechniques would avoid authoritarian, costly, and unnecessarily painful conditioning techniques, which are doomed to fail miserably. Instead, it would employ consumer-oriented exploitative superstimuli (Saad, 2013), optimized soma to fulfill the happiness and pleasure instincts—such as drugs to enhance love experiences (Earp & Savulescu, 2020)—and neotenization techniques (Gould, 1979) to exploit nurturing biases.

In sum, effective Utopians aim not to create a 'new man' as envisioned in dystopian fantasies but rather to subtly shape and harness the hereditary ultra-social traits of present humans. This path-dependence approach, best described as 'Science-based self-domestication', leverages advanced AI and behavioral science to foster a stable and apparently harmonious society; that is to say, liberated from the political cycle.

6. A final dilemma

Epistemic hubris, human suffering and political instability are recognizable features of historical Utopias.

But let’s imagine a millennial Dionysius, or a new 'Solomon’s House,' following the Mertonian norms of science and finally getting human nature right. I fear that this would not entail a renewed Straussian understanding of the 'first things' by the effective Utopians, nor a return to classical political philosophy, but rather its ultimate departure. We can only be certain that the disposition to use scientific realism to precipitate—or prevent—an effective Utopia should grant private corporations, governments, and global players a significant comparative advantage over those who do not understand or who reject AESR on the basis of moralistic fallacies and ad-hoc justifications.

Disregarding reality in the name of allegedly higher ideals was no noble lie, but the price of not noticing the truth about humans today, notably for the long-time self-deceptive liberal elites in the West, has never been so high. Militant ignorance of human nature in an age of AESR would be similar to ignorance about particle physics in times of nuclear proliferation. Conversely, neglecting, distorting with moralism, or overregulating policy-oriented AI systems based on actual knowledge about the world would continue to limit the extent of human suffering potentially inflicted by post-classical wannabe Utopians.

(*) A case in point is the aforementioned apocryphal seventh letter from Plato to Dion, which almost seems to have been written by traditional Aristotelians. The author, whoever he may be, justifies the political order in the ancient laws, reproaches his contemporaries for being “unable to live in the Dorian fashion of their forefathers,” and explicitly rejects any kind of violent revolt against the established order.

(**) By ‘Scientific realism' I mean the usual epistemic assumption that the best scientific theories 1) yield objective knowledge of observable and unobservable aspects of the world and 2) the metaphysical commitment with the mind-independent existence of the world, adding an emphasis on 3) the value of free inquiry and the dangers of ideology-based moralization for scientific progress.

References

Arslan, C. et al. (2018) Relaxed selection and mutation accumulation are best studied empirically: reply to Woodley of Menie et al. Proceedings of the Royal Society B

Barrett, D. (2010) Supernormal Stimuli: How Primal Urges Overran Their Evolutionary Purpose. W.W. Norton & Company

Bednarik, R.G. (2020). The domestication of humans. Routledge

Cochran, G. & Harpending, D. (2009). The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution. Basic books

Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. (1997). Evolutionary Psychology: A Primer. Center of evolutionary psychology

Dutton, E. & Woodley of Menie, M. (2018) At Our Wits’ End: Why We’re Becoming Less Intelligent And What It Means For The Future, Societas

Earp, B.D. & Savulescu, J. (2020). Love drugs. The chemical future of relationships. Redwood Press

Edwards T. et al. (2024). Predicting political beliefs with polygenic scores for cognitive performance and educational attainment. Intelligence Vol. 104

Fukuyama, F. (2004). State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century. Cornell University Press

(2011). Political order and political decay. FSG

Gould, S.J. (1979). A biological homage to Mickey Mouse

Hatemi PK. et al. (2014). Genetic influences on political ideologies: twin analyses of 19 measures of political ideologies from five democracies and genome-wide findings from three populations. Behavioral Genetics 44

Hawks, J. et al. (2007). Recent acceleration of human recent Evolution. PNAS 104(52)

Henrich, T. (2020). The WEIRDest people in the world. Farrar, Straus and Giraux

Huntington, S.P. (1957). Conservatism as an ideology. The American political science review Vol. 51 N.2

(1965). Political Development and Political Decay. World Politics. 17 (3): 386–430

King, S. (2020). Explaining the Role of Social Media in Political Polarization. Eastern Kentucky University

Li, P. M. et al. (2017). The Evolutionary Mismatch Hypothesis: Implications for Psychological Science. Current direction in psychological science 27

Macias, A. (2024). The evolution towards the blank slate. SSRN

Murray, C. (2020). Human Diversity: The Biology of Gender, Race, and Class. Hachette Book Group

Otieno, P. (2024). The Impact of Social Media on Political Polarization. Journal of Communication 4(1):56-68

Pinker, S. (2017). Should we fear the future of AI? Presentation at the European Parliament

Saad, G. (2013). The consuming instinct. What Darwinian consumption reveals about human nature. PubMed

Stankov, L. (2017). Conservative Syndrome: Individual and Cross-Cultural Differences. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(6), 950-960.

Sloterdijk, P. (2000). Normas para el parque humano. Siruela

Tomasello, M. (2014). The ultra-social animal European Journal of Social Psychology 44(3)

Tybur J.M. et al. (2018). Parasite stress and pathogen avoidance relate to distinct dimensions of political ideology across 30 nations. Psychological and cognitive sciences

Tuschman, A. (2014). Our Political Nature: The Evolutionary Origins of What Divides Us. Prometheus books

Wade, N. (2014). A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race and Human History. Penguin Books

Warne, R.T. (2020). Review: Crossing the Rubicon from the Social to the Biological Sciences. The American Journal of Psychology Vol. 133. No. 4

Wilson, E.O. (2009). Génesis. On the Deep origin of societies. Penguin books

Wrangham, R.W. (2019). Hypotheses for the Evolution of Reduced Reactive Aggression in the Context of Human Self-Domestication. Front. Psychol., 20

Xu X. et al. (2018). An orderly personality partially explains the link between trait disgust and political conservatism. Cognition and emotion Vol. 24